When it comes to archaeology, ground-breaking can be as literal as it is figurative. Bakewell business Archaeological Research Services is working hard to implement cutting-edge techniques that change that, as Rebecca Erskine discovers.

THE office space above Roly’s Fudge Pantry is perhaps an unlikely home for an internationally-renowned heritage company – but humble surrounds belie the ambition of the team of innovators at Archaeological Research Services (ARS). What started out 20 years ago as a solo endeavour by managing director Clive Waddington, is now a thriving business of some 70 staff. Its efforts received Royal recognition last year when it was one of only two Derbyshire recipients of the 2023 King’s Award for Enterprise.

In very simple terms, this is a business that ‘digs holes and finds stuff’. It also offers archaeological consultancy including impact assessments, building recording and conservation plans; and specialist services such as geospatial and remote sensing and artefact imaging. It is also committed to dissemination and value creation whether through academic publications, public talks or reconstructions such as the furnace for a ‘show & tell’ at this year’s Bakewell Show.

“Archaeology is very conservative by nature. It wishes to leave the environment untouched to enable archaeologists of the future to see the full archaeological period.”

The business is continually pushing to do more, and better, but innovation is problematic when it comes to archaeology. As Will Throssel, ARS’s Chief Operating Officer, describes: “Archaeology is very conservative by nature. It wishes to leave the environment untouched to enable archaeologists of the future to see the full archaeological period, including our time, who might have better investigative tools. At the same time, it seeks to make records, material and reports available to researchers and future generations. There needs to be a careful balance if archaeological research is to respect these two conflicting precepts.”

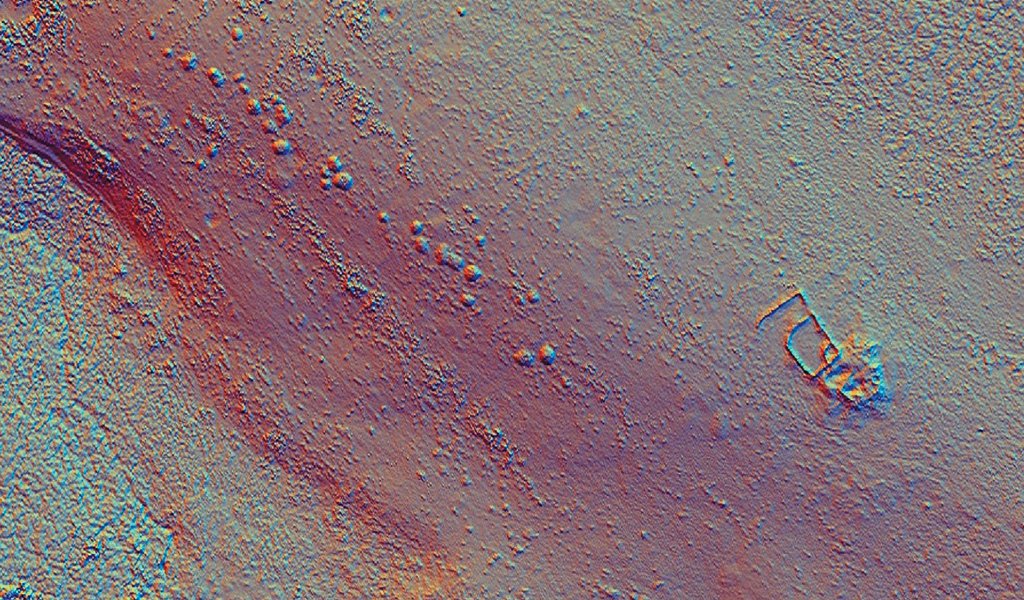

Typically, work on a large project starts with desk-based assessment which evaluates previous spot finds and records nearby. A geophysical survey is often used to map contrasts between the physical properties of buried archaeological remains and the soil in which they sit. The survey often includes magnetic techniques but this has limitations in that it does not suit some geologies and some archaeologies do not leave a footprint in the same way. Green waste spread on farmland is one such example since it dominates the signal and renders this technique useless. Drone-based surveys play an important part, too, and their ability to capture information invisible to the naked eye provides useful data in understanding what lies beneath.

Targeted trench evaluation is then undertaken but can prove problematic in some instances. Stone Age settlements, for example, had a much smaller footprint on the landscape which generally cannot be identified without a full excavation.

Developing the innovation to avoid unnecessary digs is a key objective for ARS.

A suite of different techniques provides the team with a greater understanding of what lies beneath the surface before the first spade cuts the ground. It means analysis can start earlier than might otherwise be possible, particularly on agricultural land where a dig might have to wait until a crop is harvested. There are commercial benefits, too, to this approach since there is a greater pinpointing of where the dig should take place. This is important not only for the preservation of the site but there is a two-fold advantage when it comes to carbon reduction – not only fewer carbon emissions from reduced excavator time but less carbon release from the soil itself (which happens every time it is disturbed).

There is a further human benefit, too, as Will says: “Reducing the amount of time an excavator is at work creates a much safer environment.”

HS2 work a catalyst for innovation

Projects at ARS are varied. Working on the London to Birmingham leg of HS2 was the catalyst for some of the innovation the company is now employing. If nothing else, it demonstrated, at scale, what might be possible.

Closer to home, the business has worked on countless quarries as well as local heritage sites, including the fort of Navio (meaning ‘on the river’) on the Hope Valley. Lead – in plentiful supply in this area – was favoured in Roman times for weaponry, aqueduct pipes, drinking vessels and jewellery. The Romans constructed a number of forts throughout the valley during the 1st century AD to guard this most precious of resources, including Navio, near Brough. In 2019, ARS started to investigate the vicus (widely understood to mean a small settlement such as a street, village or neighbourhood) and uncovered the remains of homes and workshops associated with the fort, as featured on the BBC’s ‘Digging for Britain’ programme.

Winning a King’s Award for Enterprise, in the highly competitive Innovation category, is testament to ARS’s pioneering approaches to archaeology, especially when it comes to non-intrusive techniques that not only improve site detection and locate “hard to find” archaeology but also improve safety, reduce carbon emissions and costs, and accelerate delivery.

The award has had a significant impact on the business. As Will says: “Everyone loves to win an award, particularly one of such international significance. It has been a source of great pride to the team that our work has the royal seal of approval, particularly as it was the first King’s Award for Enterprise (or Queen’s Award as it was previously known) to be awarded to archaeology. There are undoubtedly commercial benefits too. Our award was certainly valuable in opening up discussions in Saudi Arabia, where we have won a contract to undertake fieldwork for Neom, a new linear city of some 26,500 km² being constructed at the northern tip of the Red Sea.

“As importantly, I think it has helped others in our sector adopt a similar growth mindset. What else might be missed? Should we challenge the way we’ve always done things? These are really important questions for us all when it comes to accelerating that innovative spirit.”

Bakewell: the birthplace of Britain?

Export ambitions aside, the company is firmly rooted in Bakewell. It is a fitting location since the surrounding area offers so much archaeological significance – from the Neolithic henge monument Arbor Low to Derbyshire’s Roman forts through to the birth of the Industrial Revolution in the Derwent Valley. The plethora of quarries – owing to the fact that Derbyshire is more mineral-rich than any other county – means there is much to keep the team busy without the need to travel too far.

There is one project in particular that has piqued local interest and, if assumptions are found to be true, could be a significant boost to the Derbyshire Dales economy. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, King Edward ‘the Elder’ commanded a burgh (or town) to be built in Bakewell in AD 924. There is an explicit reference to the kingdoms of the time – including the Scots, the dwellers of Northumberland, the Danes of England and the Strath-clyde Britons – choosing Edward ‘for father and for lord’.

As Will explains: “The reference to ‘father’ implies the other kingdoms accepted Christianity and Edward as their head, and ‘lord’ their acceptance of his laws. Identifying the location of the burgh is, in fact, identifying the birthplace of Britain.

“We have a strong hunch as to where this site lies and are working with the Town Council, All Saints’ Church, and Bakewell and District Historical Society to explore how we might investigate this further, including through a community dig.”

Could such a find achieve for Bakewell what the discovery of Richard III’s body achieved for Leicester? (The year following the discovery recorded a £45 million boost to that city’s visitor economy.) Only time – and the land itself – will tell.

Editor’s Note: Information boards about ARS’s excavation of the vicus are on display at Bakewell and Castleton’s information centres.