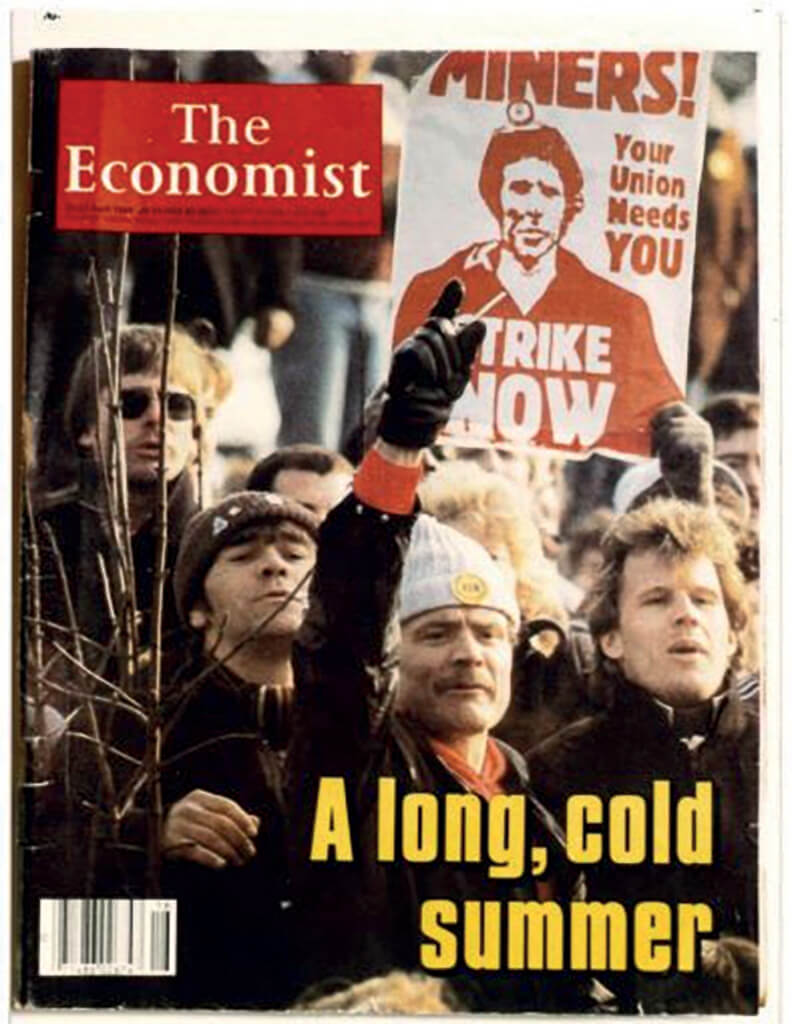

It is 40 years this month since the 1984/85 miners’ strike started, which many have since described as a ‘civil war’, as Barrie Farnsworth reports – plus recollections from Chesterfield Alderman Steve Brunt, then a striking miner, and local policewoman Sally Midgley.

ON March 6, 1984, the Conservative government announced the closure of 20 coal mines, making 20,000 miners redundant – but National Union of Mineworkers’ president, Arthur Scargill, thought they planned to close a lot more collieries.

The strike began in Yorkshire, where miners at Cortonwood colliery struck following a local vote. Then the NUM president announced a national strike on March 12, 1984, although an official ballot was not held among miners about this.

The strike, which lasted a year, was the catalyst that changed the political, economic and social history of the nation forever – and places like Derbyshire, with many pits back then, suffered more than most of the country. Mining communities were badly scarred, and some have never fully recovered.

An estimated 20,000 people were injured during the course of the strike; and three men were killed – two on the picket lines and a taxi-driver who was driving a coal miner, who had crossed the picket lines, to work.

And, since then, coal has no longer been King in areas like north Derbyshire. In 1984, there were 170 collieries in Britain, employing more than 190,000 people. But on the 20th anniversary of the strike, in 2004, there were fewer than 20 collieries, employing around 5,000 people. The North Derbyshire Area collieries did not even last that long – the last pit to close was the biggest, Markham, in 1993.

Looking Back: Alderman Steve Brunt

AT the time of the Great Miners’ Strike of 1984/85, I was a 32-year-old married man with two children, aged two and four, and the importance of maintaining a reasonably paid, full-time job in the industry was without doubt an overriding factor in my role in that strike.

Like so many young men at my colliery, I saw a real future in the industry and as a coal-face worker, I was earning good wages. But the announcement of the closure of Cortonwood Colliery in South Yorkshire, which had been given at least five years only months before, shocked us all. Our union, the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), had warned us that the Coal Board was drawing up an extensive pit closure programme and that no pit was safe.

There were rumours and counter rumours about the future of the mining industry which, if true, would undermine everything we were working for. But we felt relatively safe in the knowledge we belonged to and worked in an industry that was totally unionised, and that we would be able to repel any threats to our future livelihoods.

“We were fighting for our very existence, as we saw it.”

And so, when the call came to take action to support our colleagues across the industry, I didn’t hesitate. I was glad actually that our union the NUM was taking on the Thatcher Conservative Government who just a couple of years before had decimated the British steel industry.

I honestly thought: ‘this will be over in a couple of weeks and we could all get back to work and get on with our futures’. How wrong was I. We picketed our own pit at first (Arkwright). Fortunately in Derbyshire we were solid, every pit was out on strike, at least for the first six months or so.

Problems arose when Nottinghamshire demanded a national ballot which divided the union and eventually led to the break-up of the NUM. Should we have had a ballot? Hindsight is a wonderful thing, but at the time I thought no. This was a just cause we were fighting for, because this wasn’t about wages or working conditions, this was about our future and our children’s future. We were fighting for our very existence, as we saw it.

We soon became flying pickets and in a short space of time, Britain became a police state. We were being stopped constantly by the police and told to turn round and go home. Apart from Orgreave, of course, where the police actually directed us to the picket lines in June 1984. In effect, they set us up for a huge confrontation – which they got – because at times it resembled a battlefield.

Lots of lads were arrested on the picket lines and lots jailed, and I was eventually arrested on October 17 in a classroom at Hurst House Education Centre while attending a day-release course, but was later released without charge. I really do believe I must have been the only flying picket to be arrested in a classroom!

The most distressing part of the dispute as it dragged on for me was seeing our comrades, friends and mates return to work having given their all and, in most cases, they had been on strike for at least 6/7 months. Savings all gone and debts built up. And quite frankly, they’d given their all.

For me, it was all but over just after Christmas when the trickle back to work became a torrent. In fact, when we did eventually go back to work on March 3, 1985, only 96 of the 800-plus men who worked at Arkwright Colliery were still officially on strike and we had a plate struck with the 96 names, which is on show at the Chesterfield exhibition from March 4-27.

A very different story ten years earlier

IT IS half-a-century since Britain’s miners won a 35 per cent pay rise – and effectively brought down Edward Heath’s Conservative government.

British coal workers called off a four-week strike following the pay offer from the new Labour government, led by Harold Wilson, in what was seen as a resounding victory for the miners.

“Around 260,000 miners accepted weekly pay rises.”

The Labour offer was worth more than double the figure on offer under Edward Heath’s government. Around 260,000 miners accepted weekly pay rises ranging from £6.71 to £16.31. Face workers saw their pay rise to £45 per week – £8.21 more than their present wages.

The 16-week dispute, which saw coal production come to a complete standstill during the February 1974 strike, finally ended just 48 hours after the Conservative party was voted out of power.

A few days after the strike came to an end, the Three-Day Week restrictions were lifted on March 7, 1974. From New Year’s Day in 1974, commercial users of electricity were limited to three specified consecutive days’ consumption each week and prohibited from working longer hours on those days. Services deemed essential (ie, hospitals, supermarkets and newspaper printing presses) were exempt. Television companies were required to cease broadcasting at 10.30pm to conserve electricity.

‘What’s a woman doing here?’

RETIRED police officer Sally Midgley still remembers the onset of the miner’s strike in Derbyshire – they were moved onto 12-hour shifts instead of the normal eight.

She said: “We female officers – and there weren’t many of us in those days – were left back at our usual stations, mine was Ilkeston, to cover for the male officers who went off to police the strike itself. So we were generally ‘on the beat’ between 6am and 6pm, or a 12-hour night shift.

“We patrolled on our own – heaven forbid a supervisory officer saw you with a colleague! I recall that it used to really scare my mum Pauline, thinking that I was patrolling alone.

“I also recall that it was before the age of policewomen in trousers, we still had to wear skirts in those days.”

She recalls officers from the Metropolitan Police Force – the ones that many local miners particularly hated – were put up in what were then three accommodation blocks at the county police headquarters, Butterley Hall.

As it was before the days of sat-navs, the Met officers needed a local ‘pilot’ to take them to collieries and other places where miners were picketing – and Sally remembers being the ‘pilot’ in a police transit van on a night shift, taking around 10 officers to Shirebrook, where she had lived as a young child and where her father Keith had served as a policeman.

“Somebody at Shirebrook police station said ‘what’s a woman doing here?’ – and I was recalled to the ‘safety’ of Ilkeston and have to assume that was why I was never told to ‘pilot’ a van again,” Sally said.

She added: “I come from a mining family – my dad was a colliery electrician before he joined the police – so the effects of the strike were felt beyond my work. I still remember going to a relative’s house in 1984 and my uncle said ‘you are not welcome here’, but my aunty then said ‘she’s your niece first and is always welcome in our house’.”

Sally and her husband John, who was working in a regional crime squad when the strike started and was not involved in policing picket lines, are both now retired and living near Crich.

“Mind you, we seem to be even busier these days,” said Sally, as her and John started a ‘True Crime Investigators UK’ podcast nearly four years ago, and also deliver ‘true crime’ talks – based on real crimes from the Seventies and Eighties – to clubs and groups.

Editor’s Note: The link to Sally and John’s podcast is https://www.truecrimeinvestigators.co.uk/