Chris Drabble is a writer and photographer who ventures out into the Peak District in search of cloud inversions in autumn and winter.

CLOUD inversions are an incredible and spectacular yet elusive phenomenon that once seen, will never be forgotten.

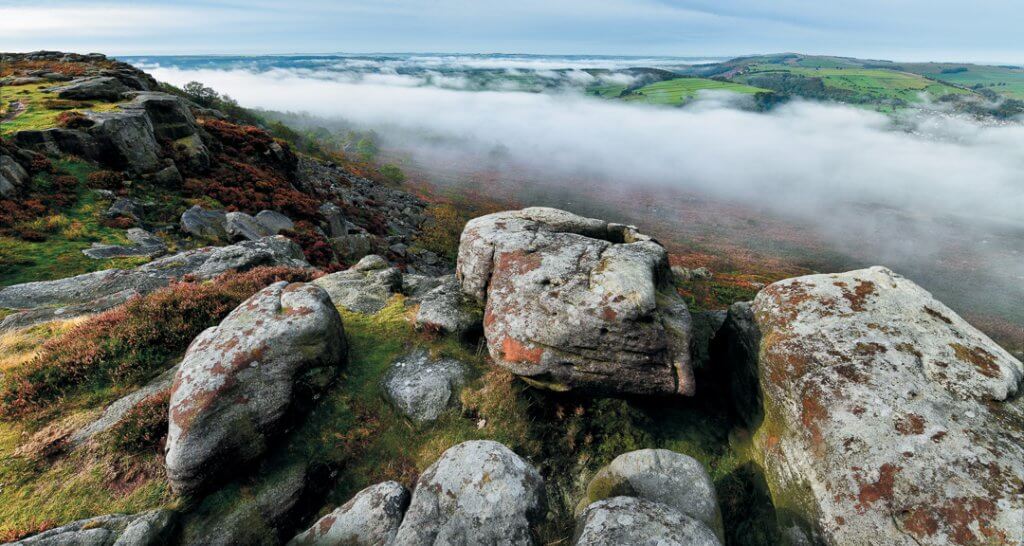

Imagine climbing a hill on a cold, foggy morning and on reaching the top you suddenly find that you’ve walked out into bright, clear skies and all around you, below your feet, is a blanket of cloud that has poured into the valleys and enveloped the landscape. Looking out across this ocean of cloud, the higher ground of distant tors and crags stand out like islands in a milky sea.

What causes cloud inversions?

The rule of thumb, under normal conditions, is that the higher you climb, the colder it gets. Conversely, cloud inversions are created by an inversion of temperature where a layer of warm air at a higher elevation traps colder air beneath it and this results in clouds forming in the lower atmosphere.

Is it easy to predict such inversions?

Cloud inversions aren’t easy to predict, but certain weather conditions are conducive to their formation, for example: cold, clear, still nights with a weather forecast for high pressure in late autumn, winter and early spring raise the probability factor by a significant degree.

How long do they last?

Cloud inversions usually disperse as the sun rises and warms the ground temperature through the day and so an early start is recommended to be in position at sunrise, if you wish to see inversions at their best.

What are the best places to see cloud inversions?

To see inversions at their best you need to be high up and above the cloud. I have seen good inversions from Kinder Scout, Bamford Edge, Stanage Edge, Mam Tor, Win Hill, Chrome Hill and Longstone Edge.

Editor’s note: Chris is a member of Bassetlaw Hill and Mountain Club and the Over the Hill Photographers Club. More of his photographs can be found at photo4me.com Alamy and 500PX.